Van Til’s Trilemma

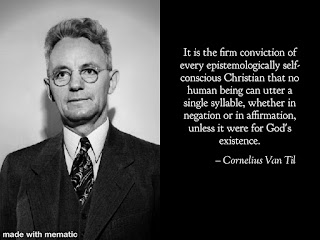

Our various epistemological endeavors as human thinkers presuppose some form of order or unity to the objects of knowledge (the “facts”). It is safe to say that the possibility of human knowledge necessitates that various relations exist between facts. These relations could range from conceptual, to logical, causal, epistemic, numerical, etc. Denying relations between facts leads to brute factuality and eventually skepticism (see here). These observations lead us to inquire as to what exactly facilitates the various relations needed for knowledge of facts to obtain. It would seem there are only three possible answers to this question. From this, we can offer a transcendental argument which I have chosen to call “Van Til’s Trilemma”. Van Til writes:

Why live in a dream world, deceiving ourselves and making false pretense before the world? The non-Christian view of science: (a) presupposes the autonomy of man; (b) presupposes the non-created character, i.e., the chance-controlled character, of facts; and (c) presupposes that laws rest not in God but somewhere in the universe.1

“Laws” here generally refers to universals, kinds, classes, or anything that is meant to relate, order, or categorize individual facts. Van Til says that the non-Christian presupposes that the relations between facts are not found in God but somewhere in the universe. Also, the non-Christian presupposes that the facts are not created by God and are hence controlled by Chance. However, for Van Til, it is God (through his eternal plan and counsel) that provides the relations between facts:

The whole meaning of any fact is exhausted by its position in and relation to the plan of God. This implies that every fact is related to every other fact. God's plan is a unit. And it is this unity of the plan of God, founded as it is in the very being of God, that gives the unity that we look for between all the finite facts.2

If the relations between facts are not established by God, they would have to be established by man. As Van Til notes:

According to the Christian story, logic and reality meet first of all in the mind and being of God. God's being is exhaustively rational. Then God creates and rules the universe according to his plan. Even the evil of this world happens according to this plan. The only substitute for this Christian scheme of things is to assert or assume that logic and reality meet originally in the mind of man. The final point of reference in all predication must ultimately rest in some mind, divine or human. It is either the self-contained God of Christianity or the would-be autonomous man that must be and is presupposed as the final reference point in every sentence that any man utters.3

From Van Til’s writings we can see that the three possible answers to the question of what facilitates the relations between facts are God, man, or Chance. Now we can sketch out Van Til’s Trilemma thusly:

If there are no relations between facts, then human knowledge is impossible.

There are relations between facts.

The relations between facts are either: (a) provided by the mind of God, (b) provided by the mind of man, or (c ) a product of Chance.

If (a), then human knowledge is possible.

If (b), then human knowledge is impossible.

If (c ), then human knowledge is impossible.

Therefore, if the facts are not related in the mind of God, human knowledge is impossible.

The first premise has been established previously. An absence of unity between facts implies epistemological skepticism. The second premise is taken for granted. We are assuming that both parties agree that human knowledge is possible and that there are relations between facts. Anyone who wishes to deny (2) would have to embrace epistemological skepticism.

(3) represents the Trilemma and it exhausts all possibilities for there are no other options. All epistemological schemes must tackle one horn of the Trilemma.

In defense of (4), it is not difficult to see how basing the relations between facts in the mind of God preserves the possibility of human knowledge. If the relations between the facts obtain in virtue of the eternal and comprehensive plan of God, then they are in principle objective, necessary, and knowable by man (with the help of divine revelation).

If one rejects God, however, and instead tries to secure the unity between facts through the activity of man’s mind, then it follows that the relations between facts are not objective, inherent, or necessary (see here). This implies that man’s attempts to unite and relate the facts are necessarily arbitrary. This is because the relations between facts would be merely internal to man’s mind and therefore subjective. This makes knowledge impossible for man merely knows what the ordering activity of his mind reflects to him and not how the facts are objectively. (5) is true.

However, if neither the mind of God nor the mind of man provides the needed unity to the facts then it must be maintained that the relations between the facts obtain merely due to “Chance”. This means that the facts just happen to be related; there’s no underlying reason or explanation for the relations that exist between them. It must be pointed out that such a notion destroys the possibility of human knowledge. A unity that is based on Chance is no unity at all. If relations obtain in virtue of Chance, then they could just as easily cease to obtain in virtue of Chance. Relations based on Chance are neither necessary, inherent, nor changeless. But human knowledge requires necessary and inherent relations to obtain between facts. As such, (6) is true and our conclusion follows.

References

Common Grace and the Gospel (Philadelphia: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1972), 195.

Survey of Christian Epistemology, 5.

Defense of the Faith, 309.

Great article! Using it and the footnotes to teach about apologetics, philosophy, and worldview in a current Sunday school.

ReplyDeleteIs there a fuller footnote for footnote three?