Does Logic Presuppose Christianity? — Part 4: The Epistemology of Logic

PART FOUR: THE EPISTEMOLOGY OF LOGIC

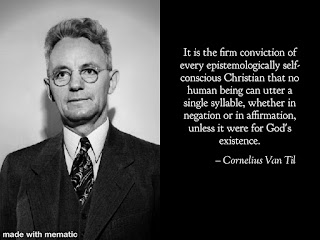

Another area which one can employ the Van Tillian argument from logic concerns the epistemology of logic. The major claim here is that the justification of logical truths and principles can only be provided on the basis of Christian Theism. We can raise the question of how exactly one justifies the truths of logic; what evidence does one have that his most strongly held beliefs about logic are true?

The justification of truths in general has traditionally fallen into two categories: a posteriori justification, and a priori justification. A posteriori justification concerns justification that is based on empirical experience of the world. Meanwhile, a priori justification concerns justification that does not need to refer to empirical experience in any way. Justification of logical truths have fallen into these categories as well.

A Posteriori Justification

Dr. Bahnsen, in his second opening statement in his debate with Dr. Stein, says:

Now if you want to justify logical truths along a posteriori lines, that is rather than arguing that they are self evident, but rather arguing that there is evidence for them that we can find in experience or by observation - that approach, by the way, was used by John Stuart Mill - people will say we gain confidence in the laws of logic through repeated experience, then that experience is generalized.

A posteriori justifications of logic propose that we come to know logical truths through experience and observation. It may be claimed that we observe successful results of inference tokens and then extrapolate to valid argument types. In general, this type of justification relies on experience and observation in some form. However, there are a few problems with such a justification of logic.

Firstly, the complexity of certain logical truths make it doubtful that one can have empirical experience of them. Where can one observe an instance of the following logical truth: “a proposition has the opposite truth value from its negation”? Where does one perceive instances of rules of inference?

Secondly, even if it is granted that one can observe certain logical truths and inference tokens, why think that such observation can be extended beyond the narrow domain of human experience? At best, we can claim that logical truths obtain as far as we know. On this view, logic loses its necessity and universality. An a posteriori justification of logic contextualizes logic to the point where it cannot be applied beyond experience; not the future, past, or possible worlds. An a posteriori justification is inadequate on the basis of these issues.

A Priori Justification

A priori lines of justification attempt to justify logic without reference to experience or observation. This line of justification may take various forms. One may appeal to things like self-evidence, intuition, necessity and analyticity, etc. However, they all fall prey to the same problem.

The problem is that if logical truth can be justified apart from experience, why should we think that logical truths have anything to do with the realm of contingent experience? As Bahnsen notes:

But if you don't take that approach and want to justify the laws of logic in some a priori fashion, that is apart from experience, something that he suggests when he says these things are self-verified. Then we can ask why the laws of logic are universal, unchanging, and invariant truths - why they, in fact, apply repeatedly in the realm of contingent experience.

Dr. Stein told you, "Well, we use the laws of logic because we can make accurate predictions using them." Well, as a matter of fact, that doesn't come anywhere close to discussing the vast majority of the laws of logic. That isn't the way they're proven. It's very difficult to conduct experiments of the laws of logic of that sort. They are more conceptual by nature rather than empirical or predicting certain outcomes in empirical experience. But even if you want to try to justify all of them in that way, we have to ask why is it that they apply repeatedly in a contingent realm of experience.

Why, in a world that is random, not subject to personal order, as I believe [it is] for a Christian God, why is it that the laws of logic continue to have that success generating feature about them? Why should they be assumed to have anything to do with the realm of history? [And] why should reasoning about history or science, or empirical experience have these laws of thought imposed upon it?

The issue is that if one confines logic to some a priori realm, then it ceases to have any connection to the world of empirical experience. Why think that the facts of the external world cohere with the system of logic in our mind? Why should the facts of the external world have these logical truths and categories imposed upon them? Why think that the external world (which has nothing to do with our system of logic) would produce repeated instances of logical truths? The problem is simple: if the justification of logic is wholly a priori then the application of logic to experience becomes arbitrary. Logic is imposed upon experience even though they both have nothing to do with each other. For this reason, an a priori justification of logic is inadequate.

The only other option seems to be to appeal to linguistic convention. However, this renders logical truths culturally relative. If logical truths are merely a function of how we choose to use language, then different cultures could, in theory, come up with different logical truths. This is philosophically unacceptable.

How, then, can the unbeliever justify his belief in and use of logic? The unbeliever must be pressed to provide an adequate justification for logic from within his worldview. The apologist must be attentive and discern what kind of justification is being offered and critique it accordingly.

The Christian justification of logic is a priori, however it does not fall into the same problems an unbelieving justification does. As we pointed out in the previous installment of this series, God is the archetypal rationality. He possess absolute internal coherence and wisdom. He has shared some of this wisdom with us by creating us in His image and granting us logic which reflects His own rationality. We know logic, then, through revelation. By being created in God’s image, we are equipped with logical capabilities with which we can reflect, in our own creaturely way, the original coherence of God’s wisdom. Our logical system is not detached from the world of experience. We exist in God’s world. Our system of logic reflects the wisdom of God. The world we inhabit is controlled by God, hence all the facts are created and controlled by God to cohere with the original system in His mind. By thinking God’s though after Him, we can, through logic, gain knowledge of the world.

Thank you for putting the time in to share this.

ReplyDelete