Epistemic Circularity: A Van Tilian’s Thoughts

It is impossible to study Van Tilian Presuppositionalism without eventually coming to the issue of circular reasoning. This is partly because one of the most common objections to Van Til’s method of apologetics is that it is circular and hence cannot be taken seriously as a defense of Christian faith. It is said that such a method gives no positive reasons to believe Christianity because it proposes that in order to defend the faith one must presuppose or assume its truth. Various (decisive) responses to this objection have been provided in the presuppositionalist literature. The Van Tilian’s response is that his method is not circular because it is indirect rather than direct. He is not concluding that Christianity is true based on premises which already assume its truth. Rather his method aims to adjudicate between worldviews transcendentally.

Another reason that one cannot avoid the topic of circular reasoning when discussing Van Tilian Presuppositionalism is that Van Tilians make the claim that circular reasoning is unavoidable—we all must reason circularly in some way. This claim has also been heavily criticized. It is claimed not only that it is false but that it contradicts the Van Tilian’s insistence that his method is not circular. In response to this the Van Tilian would make a distinction between logical circularity and epistemological circularity. He would claim that the latter is much broader than the former and that it is not fallacious, unlike the former. This distinction has also been called into question. Some have claimed that it is a distinction without a difference. Some claim that the latter collapses into the former. Some claim that the latter type is definitely avoidable and that the Van Tilian’s claim to the contrary is false. The Van Tilian’s distinction between vicious and virtuous circularity has been ridiculed as being superfluous.

What are we to make of all this? Is there really a distinction between logical and epistemological circularity? What exactly is epistemic circularity? Are there vicious circles and virtuous ones? Is circularity really unavoidable? Answering these questions and bringing much needed clarity to the discussion is the aim of this article. To do this, we shall first take a look at the notion of epistemic circularity as it is used in the philosophical literature.

Epistemic Circularity in Philosophical Literature

It is important to note that the subject of epistemic circularity is usually discussed in the context of the debate between internalists and externalists. Externalists are usually the ones who advocate for some form of epistemic circularity.

The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (https://iep.utm.edu/ep-circ/) defines an epistemically circular argument as an argument that “defends the reliability of a source of belief by relying on premises that are themselves based on the source.” However this definition is too narrow. A better definition is provided by Timothy and Lydia McGrew in their book Internalism and Knowledge:

We shall therefore say that epistemic circularity is present whenever p appears in the defense of an ascription of epistemic status to p.There are, then, two types of epistemic circularity, one applying to arguments and one to foundational beliefs. First,

an argument for p is epistemically circular in relation to a metalevel defense of Jp iff p appears at the metalevel as part of the defense of Jp.

Second,

the holding of a foundational belief p is epistemically circular in relation to a metalevel defense of Jp iff p appears at the metalevel as part of the defense of Jp.1

All this may seem a bit technical but the central idea is quite simple. p here refers to any object of belief (for example, the belief that “the sun will rise tomorrow”). Jp here refers to beliefs at the metalevel about whether or not a subject is justified in believing p. “Metalevel” simply refers to a higher order belief about p (such as “subject S is justified in believing p). Simply put, p refers to the object level while Jp (beliefs about the justifications, warrants, etc. a subject has with respect to p) refers to the metalevel.

When asked “how do you know that p?” answering the question would involve a metalevel defense of Jp. Essentially, answering the question involves providing reasons to think Jp (that you are justified in believing p) is true. Epistemic circularity, then, occurs when the object of belief (p) is appealed to or presupposed in the justification of belief. From this definition, there are two kinds: epistemic circularity involving argument for a belief, and epistemic circularity involving the holding of a foundational belief. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy’s definition of epistemic circularity is subsumed under this definition. More precisely, it is a circularity of the first kind—it involves epistemically circular arguments.

The IEP gives an example of an epistemically circular argument:

Alston (1989; 1993, 12-15) takes sense perception as an example. If we wish to show that sense perception is reliable, the simplest and most fundamental way is to use a track-record argument. We collect a suitable sample of beliefs that are based on sense perception and take the proportion of truths in the sample as an estimation of the reliability of that source of belief. We rely on the following inductive argument:

At t1, S1 formed the perceptual belief that p1, and p1 is true.

At t2, S2 formed the perceptual belief that p2, and p2 is true.

.

.

.

At tn, Sn formed the perceptual belief that pn, and pn is true.

Therefore, sense perception is a reliable source of belief.

But how do we know that the perceptual beliefs mentioned in the premises (p1, p2) are true? We would have to fall back on sense perceptions. Hence the premises of this argument rely on sense perception. In order for us to be justified in accepting the premises, the conclusion must be true. Notice that this is not the same as logical circularity. The premises themselves do not assume that the conclusion is true. Rather, the justification of the premises rely on the truth of the conclusion. The object of belief (the reliability of sense perception) is presupposed in the justification. Hence, epistemic circularity is present.

In the literature, it is a common opinion that there is something fundamentally wrong with epistemic circularity. One of the issues that is brought up with epistemically circular arguments is that they are dialectically forceless. What this means is that they cannot rationally convince an audience that is skeptical of their conclusion. The IEP puts it this way,

There is another sense of showing, that of “dialectical showing.” Showing in this sense is relative to an audience, and it requires that we have an argument that our audience takes to be sound, otherwise we would be unable to rationally convince it. If we assume that our audience is skeptical about the reliability of sense perception, it is clear that we cannot convince such an audience with an epistemically circular argument. This is so because the audience would also be skeptical about the truth of the premises. Assuming that our audience is skeptical only about perception and not about introspection and induction, we can only show to such an audience Alston’s hypothetical conclusion: if sense perception is reliable, we can show–in the epistemic sense–that it is.

A more serious objection to epistemic circularity is that it leads to an infinite metaregress. This objection, presented by the McGrews, states that epistemic circularity cannot justify beliefs because it leads to an infinite metaregress. But what is a metaregress? The McGrews define it thusly:

We can now define the metaregress as a hierarchy of defending arguments for isomorphic claims at each ascending metalevel – e.g. that Jp, JJp, JJJp, etc.2

Simply put, a metaregress is similar to what occurs at the object level when one keeps asking, in an annoyingly child-like fashion, “how do you know that”? At the object level, a proposition P is supported by another proposition Q, which in turn is supported by R, ad infinitum. In this case, at the metalevel, Jp is supported by an argument/principle (JJp), which is in turn supported by another, and so on. The idea is that if epistemic circularity occurs, then there would be an infinite loop which would fail to confer justification on the original belief p (just as circularity at the object-level fails to confer justification). The McGrews claim that if epistemic circularity obtains, then, given the metaregress, there would always be an undischarged conditional at the metalevel. This is because the externalist allows for new empirical information or contingent facts (such as the reliability of a certain belief-forming process) to arise in his metalevel argument. So, p is justified if some contingent fact obtains. But it cannot be shown that that fact obtains. As the McGrews point out,

The metaregress affixes an undischarged conditional to all of the externalist’s arguments and even to his foundational beliefs. His beliefs have positive status if something else is the case, and he can defend the claim that this ‘‘something’’ is the case if he possesses information relevant to it. But that argument itself gives positive status to its conclusion only if something else is the case, and so on. Just as a circular argument at the object level precludes ending the regress of reasons by discharging the conditional ‘‘p if (something else) . . . ,’’ so an epistemically circular argument precludes the possibility of ending the metaregress by discharging the conditional, ‘‘p is justified (warranted, etc.) if (something else) is true.3

Externalists have accepted this objection but it has been claimed that it does not stop epistemic circularity from yielding justification. Alston writes,

[S]urprisingly enough . . . [epistemic circularity] does not prevent our using such arguments to show that sense perception is reliable. ... Nor, pari passu, does it prevent us from being justified in believing sense perception to be reliable by virtue of basing that belief on the premises of a simple track record argument. At least this will be the case if there are no ‘‘higher level’’ requirements for being justified . . . such as being justified in supposing the practice that yields the belief to be a reliable one, or being justified in supposing the ground on which the belief is based to be an adequate one.4

Alston claims that epistemically circular arguments can still provide justification as long as there are no higher-level requirements for justification. As long as we are in fact justified in believing the premises of the argument, then that justification can be transferred to the conclusion. But recall that the truth of the conclusion of an epistemically circular argument is presupposes in our being justified in accepting the premises. Alston is saying that this doesn’t stop us from being justified if we maintain that all that is needed for justification is that the process be, in fact, reliable (or that the conclusion be, in fact, true) and not that we know or are justified in believing that it is reliable (a higher-level requirement).

For Alston, it does not matter whether or not it is possible to terminate the metaregress. All that matters is that the beliefs are justified and they are justified if they satisfy certain epistemic principles such as:

EP: If one believes that p on the basis of its sensorily appearing to one that p, and one has no overriding reasons to the contrary, one is justified in believing that p.5

If a belief satisfies the antecedent of such a principle, then that belief if justified—period. No higher-level requirements needed. As long as belief in the premises of epistemically circular arguments satisfy principles such as EP, then those beliefs are justified and it follows that epistemic circularity can yield justification.

The McGrews have something to say about this. For them, justification (or any positive epistemic status) requires that the metaregress must be in principle decisively stoppable. Our epistemic principles must be, in principle, “vindicable” (rationally defensible in such a way that terminates the metaregress and does not allow for rational doubt). They claim this because the contrary assumptions of externalism and epistemic circularity has a problem of arbitrariness. If we maintain that our epistemic principles cannot be defended in a way that stops the metaregress, then we have no way to distinguish genuine epistemic principles from epistemic principles such as the following:

FP: If S believes that p because p has been expressed to S by someone who wears mismatched socks, then S is justified in believing that p.

The McGrews go on to say:

It does not matter whether p often happens to be true under such circum- stances. Even if the truth of beliefs formed under these conditions were guaranteed by the continual miraculous intervention of an omnipotent deity, FP would not be a serious candidate for an epistemic principle.

Yet, like any putative epistemic principle that cannot be defended in such a way as to stop the metaregress, FP is ‘‘vindicable’’ by way of an epistemi- cally circular argument. S can assert FP and, when challenged about it, can support it by saying that it was told to him by someone wearing mis- matched socks. (As a last resort, he can even put on mismatched socks and express it to himself.) In response to the obvious question, ‘‘So what?’’ S (quickly slipping into his epistemologist’s hat and socks) can reply that the inference from ‘‘p was told to me by someone wearing mismatched socks’’ to ‘‘p’’ is justificatory in virtue of its satisfaction of the higher-level ‘‘principle,’’ FP. If pressed, one could easily invent an arbitrarily large set of such principles and use them to ‘‘reinforce’’ each other.

By this sort of reasoning, anything can be viewed as ‘‘possibly justified.’’ After all, if FP is a real metaprinciple, then those beliefs comporting with its requirements (including, in this case, FP itself) are justified. And if we consider it meaningful to speak of epistemic principles that are nonetheless invindicable except by way of such epistemic circularity, then we have absolutely no reason not to take FP, and the epistemically circular argument S gives for it, seriously. It could just be the case that FP is one of those invindicable but nonetheless genuine epistemic principles and therefore that beliefs satisfying it are in fact justified. On the assumption that real metaprinciples can be invindicable, there is simply no way to tell.6

If such clearly farcical epistemic principles can be defended by epistemic circularity, then it does seem that there is something wrong with epistemic circularity. What is the Van Tilian to make of all this? It is to this question we now turn.

Van Til, Circularity and Revelational Epistemology

With the above considerations in mind, we can now examine circularity as it appears in Van Til’s system. We can present another example of epistemic circularity—one of the second kind. This one involves the holding of a foundational belief. We can take the belief that the Bible is God’s Word for example. So,

P: the Bible is God’s Word

P is the object of belief. But what is the justification for P? Why do we believe that the Bible is God’s Word? The answer is that believe the Bible is God’s Word because it says it is God’s Word. But is this belief justified? Are we justified in believing something merely because the Bible said so? The answer is yes, our belief is justified. Why? Because the Bible, as the infallible, perfect revelation of an infallible perfect God, possesses, and is revealed to us with, intrinsic authority. Our belief in whatever the Bible says is based on this intrinsic authority. Such a belief is justified.

Here we see that the object of belief (the contents of the Bible) is appealed to in the justification. Epistemic circularity is present. Even stronger, the Bible actually justifies itself—it is self-authenticating. In the standard cases of epistemic circularity (such as the argument for the reliability of sense perception), something else is appealed to. In the case of sense perception, its track record as a reliable source is appealed to as a justification for its reliability. However, in the case of the Bible, no external contingent fact is appealed to in its justification. The fact that it is God’s Word justified our believing it is God’s Word. If it were subject to external verification, then it loses its intrinsic authority. The Bible, to be what it is, must be believed on its own authority. Van Til captured this point well when he wrote,

Bible must be true because it alone speaks of an absolute God. And equally true is it that we believe in an absolute God because the Bible tells us of one.

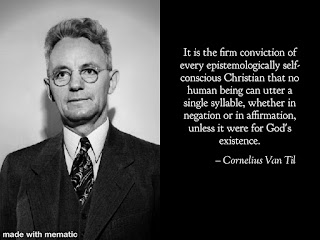

And this brings up the point of circular reasoning. The charge is constantly made that if matters stand thus with Christianity, it has written its own death warrant as far as intelligent men are concerned. Who wishes to make such a simple blunder in elementary logic, as to say that we believe something to be true because it is in the Bible? Our answer to this is briefly that we prefer to reason in a circle to not reasoning at all. We hold it to be true that circular reasoning is the only reasoning that is possible to finite man. The method of implication as outlined above is circular reasoning. Or we may call it spiral reasoning. We must go round and round a thing to see more of its dimensions and to know more about it, in general, unless we are larger than that which we are investigating. Unless we are larger than God we cannot reason about him any other way, than by a transcendental or circular argument. The refusal to admit the necessity of circular reasoning is itself an evident token of opposition to Christianity. Reasoning in a vicious circle is the only alternative to reasoning in a circle as discussed above.7

So epistemic circularity is present in Van Til’s revelational epistemology. Also, it seems that our justification for believing the Bible is conditional—it depends on some external fact. In essence, if the Bible is indeed God’s Word, then we are justified in believing it upon its own authority. The Bible has this intrinsic authority which justifies our belief only if it is in fact God’s Word. But how do we discharge this conditional? Also, it seems obvious that our argument is not dialectically forceful. It would not convince a skeptic who does not believe that the Bible is God’s Word. Lastly, we seem to be advocating an epistemic principle similar to this:

RP: if a subject believes p on the basis of divine revelation, then that subject is justified in believing p

The Bible is part of revelation but revelation extends beyond the Bible. The point is that the revelational epistemologist seems committed to RP. But what is his reason for accepting RP? There seems to be a metaregress looming. Can we terminate the regress? Or do we not need to terminate it? Is our principle indefensible then? If so, what about the charge of arbitrariness?

It is at this point that we must introduce an even broader type of circularity. This is not mere epistemic circularity. We can call this type of circularity epistemological or worldview circularity. To the charge that we have an undischarged conditional in our argument, the Van Tilian can simply retort “upon whose worldview is the conditional undischarged “? This retort is not available to the secular externalist epistemologist because he neglects holistic worldview considerations which implies that his conditional (that sense perception is reliable, for example) is a “brute” fact—not subject to interpretation by a larger framework or worldview. (Not to mention that such a conditional is not dischargeable on anything other than a Christian basis)

The Van Tilian, however, has no such problems. When pressed on how he discharges his conditional, he will appeal to his overarching worldview system—the Christian worldview—within which the “conditional” is a given, a presupposition. Ah, but the charge of circular reasoning can be raised again. This is the epistemological or worldview circularity. However, it must be pointed out that the skeptic who does not grant this given is also engaging in circular reasoning. To claim that the conditional is undischarged is simply to beg the question against the Christian.

Worldview circularity, then, is unavoidable. Everyone has a worldview and everyone has foundational presuppositions that make up that Worldview. When it comes to arguing over one’s ultimate commitments, circular reasoning cannot be avoided. The Christian tskes the divine authorship of the Bible for granted. Likewise, the skeptic takes it for granted that the Bible is not divinely authored or leaves it as an open question. But to even leave it as an open question is to presuppose that the Bible is not divine authored. Neutrality is impossible. Both sides take certain things for granted and cannot avoid begging the question against each other when it comes to ultimate commitments. Bahnsen captures this point well,

But at base, when one is giving reasons for his fundamental outlook on reality and knowledge he will appeal to some personal authority: his own mind, an esteemed scholar, a group of thinkers, the majority opinion, or God. Providing that no mistakes have been made in logical calculus or observation, a difference in personal authority will always lie behind an argument that is at an impasse. Disagreements in world-view (the axis of metaphysics-epistemology-ethics) finally reduce to an absolute antithesis in personal authority.

Until one’s authority structure changes, his ultimate philosophic position will remain unaltered. Therefore, all argumentation between non-Christian and believer must inevitably become circular, beginning and ending with some personal authority (and not a question of epistemology or metaphysics abstracted from the other).8

Worldview circularity occurs as a result of the consistency of a system. Any consistent worldview must be circular. This is because one’s worldview—one’s ultimate commitments—regiment what conclusions one draws, what one accepts as evidence, what one takes as unquestionable, etc. To accuse the Van Tilian of circularity at this point is just to accuse him of being consistent with his professed worldview. It is this kind of circularity Alan Musgrave was referring to when he wrote:

Suppose the fallibilist succeeds in showing that fallibilism withstands serious criticism or withstands it better than rival theories, and concludes that we are justified in adopting it. This is to show that fallibilism is reasonably believed by fallibilist standards. It is to argue in a circle.

I know of no convincing answer to this objection. At this level of abstraction circular reasoning is difficult to avoid. Nor are the alternatives to it any more palatable…there will come a point when we either argue in a circle (show that belief in S is reasonable by standards S* and that belief in S* is reasonable by standard S) or invoke some standard which is not reasonable by any standard. The only real alternatives in the matter are circular reasonings or irrationalism about your theory of rationality. I prefer the former – just.9

What about the charge that epistemic circularity is dialectically forceless? To that, we would agree that it is. It is not meant to be forceful against a skeptic. An epistemically circular argument only works within a consistent system and it merely shows the consistency of that system.

How about the charge of an infinite metaregress and arbitrariness? How do we defend RP?

First of all, there is no infinite metaregress because RP is beyond rational doubt. In other words, RP is knowable a priori. Divine revelation from a perfect infallible God is enough to justify a belief. In fact, it is the highest form of justification any belief can have. Revelation confers maximal warrant on a belief—whatever is revealed is epistemically certain. This observation shows that the McGrews’ arguments against epistemic circularity have no force against the revelational epistemologist.

But another charge of arbitrariness can be raised. What about other religious epistemologists that may posit similar epistemic principles? How are we to defend RP against such? The answer is simple: transcendental argument. We contend that only Christian revelation is self-authenticating. We subject competing claims of revelation to transcendental analysis and show that they are not rational. Hence, the charge of arbitrariness is answered.

Conclusion

The topic of epistemic circularity is a hot one in contemporary epistemological debates. Strong objections have been raised against the appropriateness of epistemic circularity. However the Van Tilian has. I thing to fear—these objections have no force against a truly Revelational Epistemology. That’s because it only the Christian worldview that presents a truly absolute God. And only a Christian worldview presents a truly self-authenticating revelation.

References

1 Timothy & Lydia McGrew, Internalism and Knowledge, 67

2 Ibid., 68

3 Ibid., 78

4 W. Alston, The Reliability of Sense Perception, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1993, p. 16. Cf. ‘‘Epistemic Circularity,’’ in Epistemic Justification, pp. 330–31, 334–35, 348–49.

5 Alston, ‘‘Epistemic Circularity,’’ in Epistemic Justification, p. 331

6 Timothy & Lydia McGrew, Internalism and Knowledge, 81-82

7 Cornelius Van Til, Survey of Christian Epistemology,

8 Greg Bahnsen, Presuppositional Apologetics,

9 Alan Musgrave, Common Sense, Science, and Scepticism, 294-295.

Comments

Post a Comment