How Do We Know Laws of Logic Are True?

A few days ago, I made the following post on Facebook:

If logical truths are knowable, then Christian theism is

true.

Logical truths are knowable.

Therefore, Christian theism is true

One comment on that post went like this:

“An intelligent unbeliever would have a bit of a field day with this.

Why does your conclusion, above, necessarily follow from the premise?

We could just start making up any "if, then" statements here, but that doesn't make it ok.

I'm kind of confused on this one.”

I gave a brief response to the comment but I thought it would be a good idea to flesh out my thoughts on this here.

So, what is the justification for the idea that if logical truths are knowable, then Christianity is true?

The best way to approach this would be to ask ourselves: how do we know logical truths?

Logical truths here refer to truths about the relationships between propositions, rules of inference, so-called laws of logic, etc. Such truths are usually taken for granted and seen as common sense. But how do we know that any of them are true? How do we know, for example, that a proposition and its negation always have opposite truth values?

If we think about it, we would see that there are only two possible ways we could come to know such truths - we either know them by analysis, or we know them by synthesis. I’ve talked about these concepts before in a previous article:

In the analytic method, the object of knowledge is wholly dependent on the subject of knowledge and as such, the subject gains knowledge of the object by simply analyzing their own mind. An example would be an author’s knowledge of their characters. All George Lucas needs to do to know the height of Luke Skywalker is to consult his own mind. This is because the object of knowledge (Luke’s height) is dependent on his own rational activity.

In the synthetic method, the object of knowledge is independent of the subject of knowledge and as such, the subject must investigate or experience a mind-independent world in order to know the object. Our knowledge of most things falls into this category. I cannot know how many grains are in a bag of rice by just consulting my mind - I actually have to count. This is because my mind does not determine how many grains are in the bag.

Based on this explanation, we see that the method of knowledge is dependent on the relationship between the subject and object and vice versa. In other words, if we claim to know logical truths by analysis, the implication is that logical truths are dependent on our mind. And if we claim to know them by synthesis, the implication is that they are independent of our minds. But both these methods have their problems.

The analytical method of knowledge entails that our minds determine logical truths. The problem with this is that our minds do not determine the facts of the contingent realm of experience (history). As such, there is no way to guarantee that logical truths (which are determined by our mind) have application to the temporal realm (which is mind-independent). Basically, our minds make up these logical rules but have no way to enforce those rules on the world. Logical knowledge reduces to nothing more than knowledge of a fantasy world of our own making.

The synthetic method does not fare any better. Synthetic knowledge of logical truths entails that logical truths are independent of our minds. The problem here, though, is that logical truths are universal in scope - that is to say, they can apply to multiple particulars and can have multiple instances. The law of non-contradiction, for example, isn’t just about a single proposition - it is about multiple (or perhaps, all) propositions. And to know a universal truth using the synthetic method requires one to experience every single instance of that truth. How can I know through synthesis that there are no true contradictions without experiencing every single contradiction and verifying that all of them are false? Without universal experience there is always the possibility that a universal truth is false. And no human possesses universal experience.

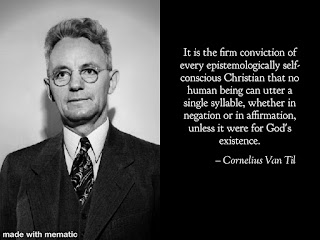

As we have seen, neither analysis nor synthesis can provide knowledge of logical truths. But these problems only arise if we leave God out of the picture. God’s knowledge is purely analytic and He can reveal things to us. We do not need to control the temporal realm to be sure that our logical system applies to the facts. God controls the facts of history and as long as we rely on His revelation, logical truths will always yield fruitful knowledge of the world. In summary, logic presupposes Christianity.

This is a short version of my thoughts on the matter. For further reading and better understanding, I recommend you check out Chapter Six of The Best Argument for Christianity where I dive deeper into these ideas. You can get it here.

God bless!

Comments

Post a Comment