Unbelievers Can’t Answer This Simple Question

There are many ways to illustrate the futility of unbelieving philosophy but I think one of the coolest ways to do that is to pose a simple question. Unbelievers cannot provide a good answer to the simple question:

why do you believe gravity will apply 20 seconds from now?

In truth, this can be applied to any belief we have about the natural world. Any answer to such a question would in one way or another rely on past experience.

The argument is something like this:

I experienced the force of gravity every single day my life

I experienced the force of gravity on Monday

I experienced the force of gravity on Tuesday

I experienced the force of gravity on Wednesday

I experienced the force of gravity on Thursday

Therefore, I'll experience the force of gravity on Friday.

The obvious issue with this is that it is logically invalid. There's no contradiction involved in accepting the premises and denying the conclusion - the conclusion does not necessarily follow from the premises. Of course, one can point out that this isn't a problem since the argument is not deductive but rather inductive. And as such, the premises serve to increase the probability of the conclusion. So, the more the sample size, the higher the probability and confidence with which we can draw the conclusion, or so the argument goes.

But the problem is even deeper than mere invalidity. But rather, since the particular experiences listed in the premises of the above argument are independent of one another, there's nothing to connect them together and also to connect them to the conclusion such that we can even say that the conclusion is probably true. This is the age-old Problem of Induction, and it concerns how we can rationally go from past experience to things which we have never experienced.

There's no necessary connection between the premises of an inductive argument such that we can move beyond the present testimony of our senses to draw conclusions about (with any degree of probability) unobserved instances.

Now, if we had an extra premise that informs us that future experiences will generally conform to past experiences then we can have support for expectations about the behavior of gravity on Friday. But another problem arises as to how such a premise can be rationally justified. No rational justification is forthcoming - at least from an atheistic standpoint. As such, atheists cannot justify their belief that gravity will apply even a second from now. They just arbitrarily and irrationally do so.

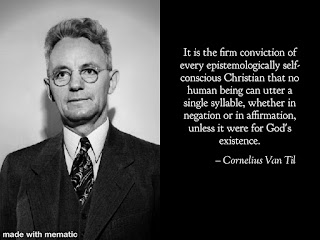

The problem of induction can be brought up in light of the unbeliever’s rejection of the Christian worldview. The unbeliever has a problem of induction while the Christian does not. The Christian can justify his belief in the uniformity of nature from within his worldview since God created and controls every single event in the world. God directs and governs creation to exhibit order and regularity and he has revealed to us that he does so. So the Christian can believe the future will be like the past, that the sun will rise tomorrow, that gravity will apply 20 seconds from now, and a whole host of other things through induction. The atheist cannot even know the simplest fact through inductive reasoning.

This is one of many illustrations of the folly of unbelief. The problem of induction is a great way to demonstrate the transcendental necessity of Christianity. To learn more about it, I recommend grabbing a copy of The Folly of Unbelief where I take a closer look at it.

God bless!

Comments

Post a Comment