Atheism Is Rationally Indefensible… Here’s Why

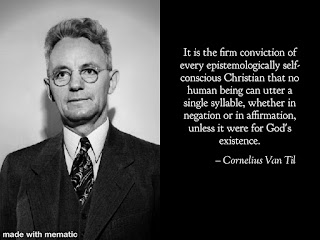

In this post I’m going to provide a quick and powerful argument for the claim that atheism is self-defeating. This is so because if atheism is true, then atheism is rationally indefensible. The particular argument I’m going to be presenting can be re-formulated and repurposed to refute a variety of worldviews, but I am going to be deploying it specifically against atheism. It could also be repurposed and used to positively argue for Christian Theism. I will leave that task to the astute Van Tilian reader.

The argument goes like this:

The actuality of skeptical scenarios entail that no beliefs possess positive epistemic status.

If (1), then in order to rationally assign a positive epistemic status to any belief, one must be able to decisively rule out skeptical scenarios.

A subject can only decisively rule out skeptical scenarios if: a) said subject is a Self-Sufficient Knower (SSK), or b) said subject has epistemic access to information from a Self-Sufficient Knower.

Therefore, the existence of a SSK is a necessary condition for the ruling out of skeptical scenarios.

If atheism is true, no SSK exists.

Therefore, if atheism is true, no subject can decisively rule out skeptical scenarios.

Therefore, if atheism is true, positive epistemic status cannot be rationally assigned to any belief.

Therefore, if atheism is true, belief in atheism cannot be rationally said to possess any positive epistemic status.

The argument is valid. (4) follows from (3), (6) follows from (3)-(5), and (7) and (8) follow from all the previous premises.

I also believe the argument is sound. The most controversial premises are (2) and (3). (1) and (5) are definitional, and the rest of the premises are conclusions from previous premises. Before we go ahead and defend (2) and (3), let us clarify a few terms.

A skeptical scenario may be defined as any state-of-affairs that renders it impossible that a belief possesses positive epistemic status (from justification, to warrant, to rationality, to plausibility, to probability, etc.). An example would be a world in which a Cartesian Demon, who constantly makes sure everyone’s judgments are in error, reigns supreme.

A Self-Sufficient Knower (SSK) is a subject who’s existence and knowledge do not depend on, and are not influenced by, anything external to it.

With these in mind, let’s jump into defending our premises.

Defending the Second Premise

The second premise states that “if the actuality of skeptical scenarios entail that no beliefs possess positive epistemic status, then in order to rationally assign a positive epistemic status to any belief, one must be able to decisively rule out skeptical scenarios.” But why think that this is true? Does it not seem false on the face of it? Let us consider a similar case to help us understand it.

Consider God and Peter the Necessarily-existing God-eating Penguin. Peter always eats God and Peter exists in all possible worlds. The actuality of Peter would seem to imply the non-existence of God. But not just that. Since Peter exists necessarily, his existence would entail the impossibility of God’s existence!

Our second premise, applied to this case, would be “if the actuality of Peter entails that God does not exist, then in order to rationally affirm the existence of God, one must be able to decisively rule out the existence of Peter”. But is that true? It doesn’t seem so. If one has independent reasons to rationally affirm the existence of God, then one does not need to rule out the existence of Peter. In fact, establishing God establishes that Peter does not exist. Furthermore, it would seem that, if our second premise is correct, then one must always refute a nearly infinite number of possible states-of-affairs that are incompatible with a certain state-of-affairs in order to rationally affirm that state-of-affairs. But that seems false. Hence, our second premise is false.

Essentially, the second premise is false because one can rationally affirm X without ruling out not-X scenarios if one has positive, rational reasons for X. This is true in most cases.

However, we can point out that in this case it is not true. To rationally affirm that a belief B possesses positive epistemic status (X) without ruling out skeptical (not-X) scenarios, we would need to possess positive, rational reasons R for affirming that B possesses positive epistemic status. But notice that to do so, we would need to rationally assign positive epistemic status to R. To do so, we would need rational reasons R’. But to assign positive epistemic status to R’, we would need rational reasons R’’, and so on ad infinitum. Hence, it is impossible to rationally assign a positive epistemic status to any belief without decisively ruling out skeptical scenarios. Our second premise has been adequately defended.

Defending the Third Premise

We can now move on to defending the third premise of our argument which states that “a subject can only decisively rule out skeptical scenarios if: a) said subject is a Self-Sufficient Knower, or b) said subject has epistemic access to information from a Self-Sufficient Knower.” Why think that this premise is true?

It seems obviously true. For any belief, there is a possibly infinite number of skeptical scenarios that undermine the positive epistemic status of that belief. No finite knower can hope to rule them all out. Not to mention, to decisively rule out skeptical scenarios would require a subject to possess knowledge about the very nature of ultimate reality. How can a subject attain such knowledge? A finite knower and a knower for whom knowledge of all things is possible are in the same boat since their beliefs about the nature of ultimate reality could still be undermined by skeptical scenarios. For a subject to gain knowledge of the very nature of ultimate reality, that subject must be in control of all facts. That is, such a subject’s knowledge of the facts must not depend on anything external to that subject. The subject must be a Self-Sufficient Knower. If the subject was not self-sufficient, there could be factors and states-of-affairs beyond its control that ensure that it fails to have knowledge. For a subject to know ultimate reality, and decisively rule out skeptical scenarios, that subject must either be a Self-Sufficent Knower, or possess information from a subject who is. Our third premise has been defended.

Conclusion

With premises (2) and (3) adequately defended, we can rationally conclude that atheism is self-defeating. If atheism were true then one would not be able to rationally affirm that it is reasonable, justified, or warranted. Hence, atheists own defenses of atheism presupppse that their view is false.

If you enjoyed that and want to see more powerful arguments against all forms of unbelieving thought, consider getting my book, The Folly of Unbelief here.

You just said a bunch of nothing. If god was a reality how could it not be known?. The fact that no one has ever seen or spoken to a deity that floats around hidden from everything is more than enough proof that the claim is pretty much stupid. If I make up some super hero no one can see,touch,or hear how can it be discredited? It cant like god they dont exist and therefore cannot be proven.

ReplyDeleteIf something can't be observed that means it doesn't exist? What?!?!?

DeleteHave you ever seen a subatomic particle? How about gravity? Time? The mind? Abstract objects like numbers? What does the Mandelbrot set look like under a microscope? How about possible worlds? What about the concept of truth? Can you measure aesthetic beauty?

Most importantly: do you have any idea how ignorant this comment makes you look?

Unfortunately, the entailment that must be true in order to defend Christianity, is that you in fact DO have access to an SSK. And you don't. You say you do, because you have to say you do, but there is no way you can demonstrate that to be the case. Therefore, what the christian claims as their basis for "knowing" it's true is unsubstantiated and the conclusion of the christian god existing might be valid, but it definitely isn't sound.

ReplyDeleteEssentially, "revelation" is unfalsifiable, and thus in turn undemonstrable. Which means the proposition is just as likely true as it is not true, like heads or tails. I can claim heads, you can claim tails. But until the coin is flipped, the truth of the result is unknowable to either of us. And when something is unfalsifiable, the coin cannot ever be flipped. So that knowledge is, at best, propositional. All either of us can know is that it will land on heads OR tails, but neither of us can ever know which is ACTUALLY the case.